Frameworks to Facilitate Crucial Conversations

We all have those conversations we are even avoiding or which usually get into an emotional debate with hurt feelings. The book, Crucial Conversations offers tools and practices to handle these dialogues better.

I am a semi-professional people pleaser, so my default way of "problem-solving" is to avoid hot topics and suffer the consequences later. Bringing problems to the surface and solving them are crucial for our personal and professional lives.

To resolve this conflict in my life I picked up Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High. I was hoping to get some useful advice with a bunch of stories (just like in usual non-fiction books), but I was surprised: the amount of practical knowledge packed in this book is hard to comprehend.

Though it is great to read about areas you would like to improve at the end of the day it comes down to practice. I intend to use the learned concepts and suggest you do the same.

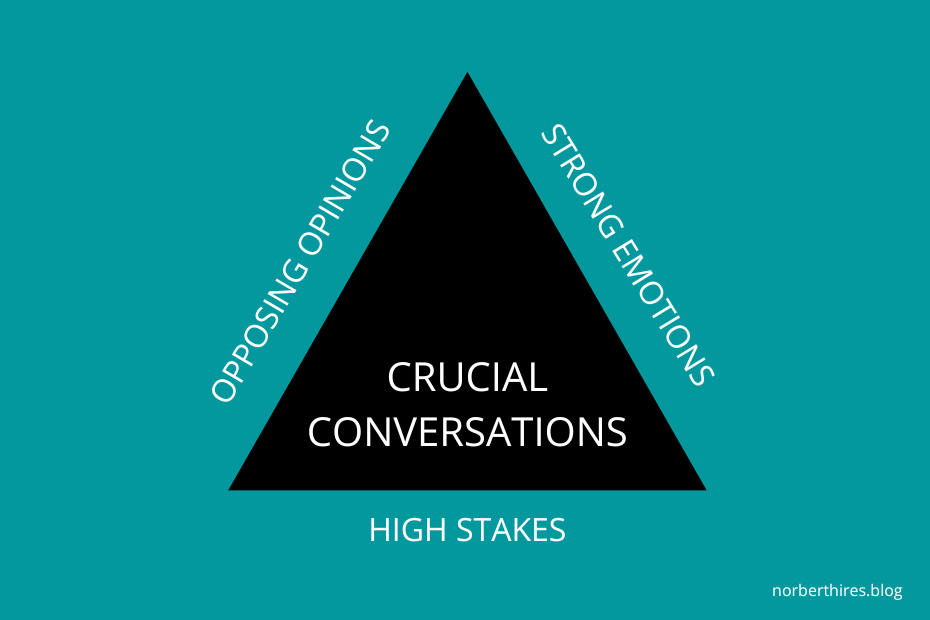

What is a Crucial Conversation?

Crucial conversations are situations when we have opposing opinions which are accompanied by strong emotions and the topic in discussion has high stakes. The unfortunate reality of crucial conversation is that when the stakes are the highest we tend to do our worst.

Though we are not good at Crucial Conversations, our ability to engage in them determines the quality of our relationships and the performance of our organizations.

"You can measure the health of relationships, teams, and organisations by measuring the lag time between when problems are identified and when they are resolved."

According to the authors, you can predict with 90% accuracy whether a project will fail based on whether the people engaged in the project can hold relevant crucial conversations. Can they speak up if they are understaffed? Can they signal that the schedule is unrealistic?

Crucial Conversations make or break companies.

- In the worst companies managers don't have the courage to hold crucial conversations with bad performers. They rather ignore them and transfer them within the organization.

- In good companies, everyone is accountable for their decisions. Managers take care of bad performers which is better for the organisation and for the individual as well.

Crucial Conversations start with people finding a way to get all the relevant information out in the open in a respective way.

In the book, there is the story of a CEO who presents a plan to move some facilities of the company to a remote location. The plan does not make any sense but it looks like no one wants to share this, since the CEO proposed the change. But one leader speaks up, he shares how much he values the work of the CEO, but he also shares his concerns on whether the CEO wants to move the facilities to this remote location because it is closer to his hometown. The CEO takes it to his heart, but after thinking it through thanks the leader for pointing this out and backs off.

But how do we start engaging in Crucial Conversations?

First, we should think before we open our mouths.

What to do before you open your mouth?

Choose Your Topic

Crucial Conversations are the most effective when they are focusing on one issue. Human interactions are complex and targeting multiple problems during one conversation can make it impossible to resolve conflicts.

Choosing one topic does not mean that choosing the topic at hand, but finding the real reason behind the problem and targeting that topic.

Ask yourself:

"What's the real issue I need to address?"

A person who is skilled at choosing the right topic is skilled at three distinct skills.

He knows how to

- unbundle,

- choose,

- and simplify the issues.

Unbundling means identifying whether it is a content, pattern, or relationship problem we are touching.

- Content: The first time the problem comes up, it is a content problem without far-reaching consequences.

- Pattern: When the same problem occurs several times, we have a pattern. The problem at this stage is not just that there is an issue at hand, but that it occurred several times.

- Relationship: If patterns escalate they can impact the relationship. You can lose your confidence, and trust in your colleague or partner.

"The first time something happens, it's an incident. The second time it might be coincidence. The third time, it's a pattern."

After unbundling the problem at hand we usually get several issues. It is worth focusing on the most pressing one without diving into the rest.

Relationships are messy.

Summarising complex problems is even messier, but articulating the definition of the problem in as few words as possible increases our chances of solving the problem. The more words you need to express a problem, the less prepared you are to tackle it.

Start with heart

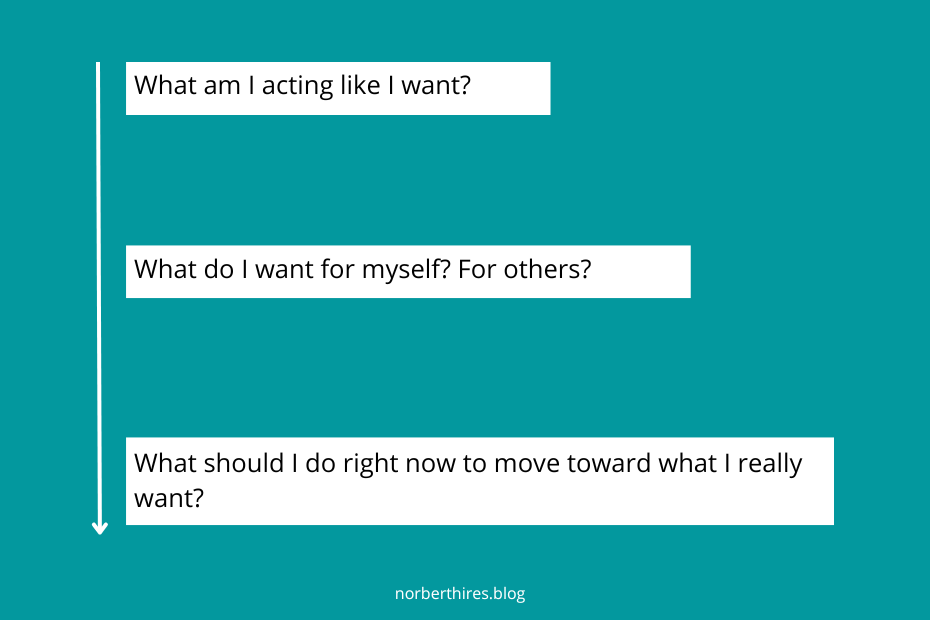

In emotionally charged situations we often self-sabotage our crucial conversations by focusing on the wrong thing. Instead, the authors suggest to focus on what you really want.

When you feel driven towards violence during a conversation ask yourself:

- "What am I acting like I want?"

- Then clarify: "What do I want for myself? For others? For the relationship?"

- And finally, ask: "What should I do right now to move toward what I really want?"

Usually, we don't want to hurt someone with mean insults or punish them with silence. We want to resolve the problem that got us into the heightened situation the first hand.

The authors call our tendency to fall into these two behaviors (violence or silence) during Crucial Conversations as the Fool's Choice. But in reality, there are more options than violence or silence if we make the effort to find them.

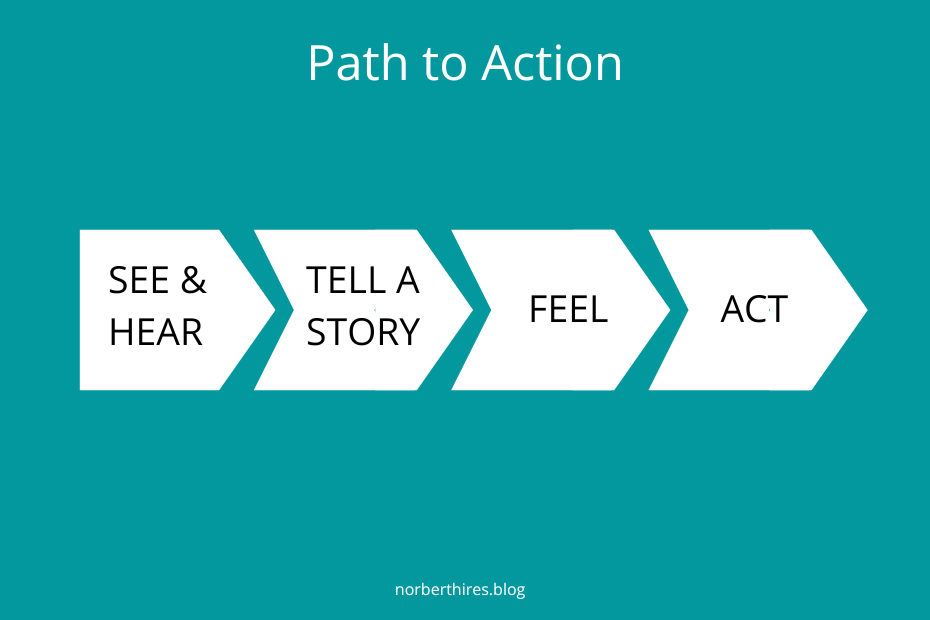

Master my stories

The best discussion partners are not the hostages of their emotions but neither do they suppress their emotions. Instead, they act on their emotions.

If someone is hurting you with mean jokes, then hiding your dislike rarely works, because you will act on it involuntarily anyway. Instead, you should acknowledge your emotions and find a way to change it.

- You have to act differently first,

- To do that you need to feel differently,

- And to feel differently you need another story.

We tell ourselves clever stories that we believe are helping us process the events around us, but often they serve only as an excuse to do the easy things instead of the right ones.

There are three main archetypes of clever stories we often fall into.

- Victim stories: When you are telling a Victim story you intentionally downplay the role you had in the problem and you act as the victim of circumstances.

- Villain stories: In Villain stories we exaggerate the bad intent or stupidity of others.

- Helpless stories: In Helpless stories, we act as if we didn't have any influence on the turn of events, and we justify our actions this way.

The common point between the three-story types is that they are incomplete stories. We intentionally miss out on details to shape the story more in line with our narrative.

To solve this small lie of ours, we should expand our stories with the details we missed out on originally.

We should turn our clever stories into useful stories.

- Turn victims into actors: Find ways you could have contributed to the situation with your behavior, actions, or non-action. It is rarely the thing that you have no role in the problem at all.

- Turn villains into humans. Ask yourself the question about your supposed villain: "Why would a reasonable, rational, and decent person do what this person is doing?" Humanizing. the villain can lead closer to the truth.

- Turn the helpless into the able. If you find yourself in a helpless story ask yourself what do you really want and how can you get closer to that.

How to open your mouth?

First of all, we should avoid controlling the conversation. Interrupting others, repeating our supporting evidence, and overstating numbers are ways to hijack a crucial conversation.

Instead, we should make the conversation safe by finding

- a mutual purpose,

- and ensuring mutual respect.

Having a mutual purpose means that we believe our conversation partner cares about our concerns. If not you should make that fact the topic of your crucial conversation, and not proceed until there is no mutual purpose.

Respect is built out slowly and there are practices you can utilize during the conversation to keep it respectful:

- Share your good intent: Stating that your intent is serving the other party serves as the foundation of the conversation.

- Apologize when appropriate: We make mistakes, and we generate false assumptions during the conversation that can decrease the feeling of safety. Apologizing for these mistakes can help us restore the safety of the conversation.

- Contrast to fix misunderstandings: During contrasting you make a statement about what you intend to achieve with this conversation and what you do not plan to. You clarify your purpose and make your motives clear this way which adds to the safety of the conversation.

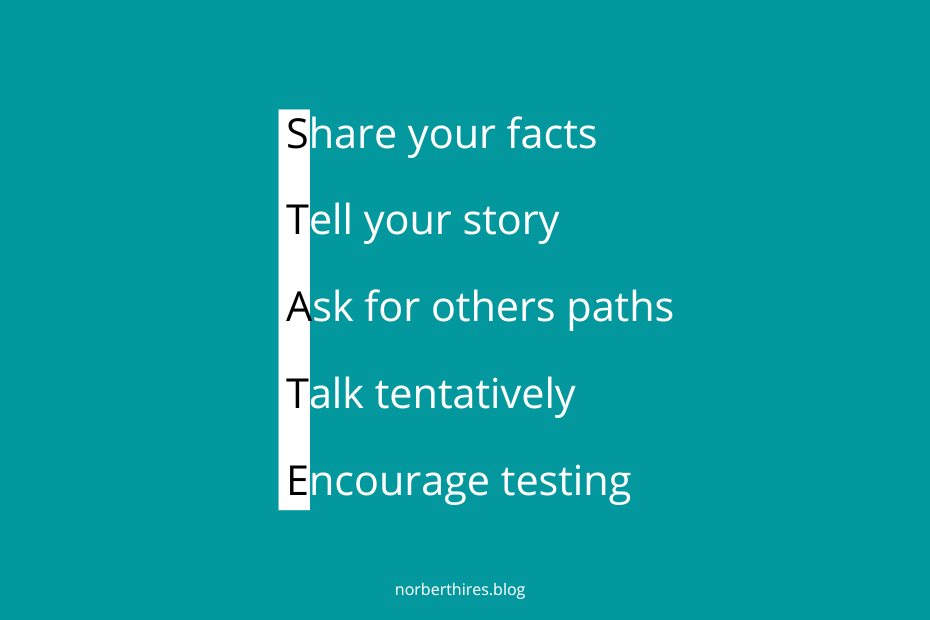

STATE my path

When you make an environment safe for crucial conversations it does not mean that it will stay the same during the heated topics of the conversation. Discussing high-risk topics means we need to stay careful during the "Path to Action" line.

To stay on the safe side we should STATE our path, aka use the advice which makes the acronym:

- Share your facts: If you are missing money from your wallet and you suspect that your conversation partner stole it you usually start with some emotionally charged statement like: "You little liar, I trusted in you and you stole from me!" This immediately makes the conversation unsafe. Instead of telling our perceived story we should focus on the facts and invite the other to find alternative stories: "100 euros are missing from my wallet. Can you help me find out what happened?".

- Tell your story: Instead of starting with your story help others to see the situation from your point of you and and share your story as the possible best story you could come up with, but not as a sure story.

- Ask for others' paths: After sharing the facts and showing our side of the story invite others to create alternative stories to get to know what you are missing and arrive at a truer story.

- Talk tentatively: When sharing a story be confident but show humility at the same time. Instead of expressions like "The fact is... Everyone knows.... The only way to do this...That's a stupid idea." use "In my opinion... I believe... I am certain...I don't think it will work."

- Encourage testing: When you invite others to contribute, make sure to emphasize the need for opposing viewpoints to avoid the Fool's Choice. Sometimes you should play the devil's advocate and model disagreeing with your own views.

Explore other paths

After stating our path we should honestly invite others and we should do our best to truly understand their points of view. Most people when they hear opposing points of view, become furious, but to have a good conversation we should be curious about opposing views.

To encourage others to share their story we can use 4 power listening tools described in Crucial Conversations:

- Ask: When we show genuine curiosity and ask questions about others' stories they become less defensive. They are less likely to stay silent or turn to violence if we ask honest questions. Asking also means we stop talking and let others fill the pool of meaning.

- Mirroring: Sometimes we should play the role of a mirror and share how we interpret others' emotions and actions. This practice is even more useful when someone is sending contradictory signals (f.e: He says everything is good, but behaves differently).

- Paraphrase: When you are sure you know how the other is feeling you can build additional safety by repeating their story in your own words. You can start this with an introduction like "Let's see if I get this right".

- Priming: Priming in the context of an old-fashioned pump means that first, you have to pull some water into the pump to get it running. It works the same in conversation if your partners are reluctant to open up. Sometimes you have to guess what they are thinking, and how they are feeling and have to put those on the table for them to open up.

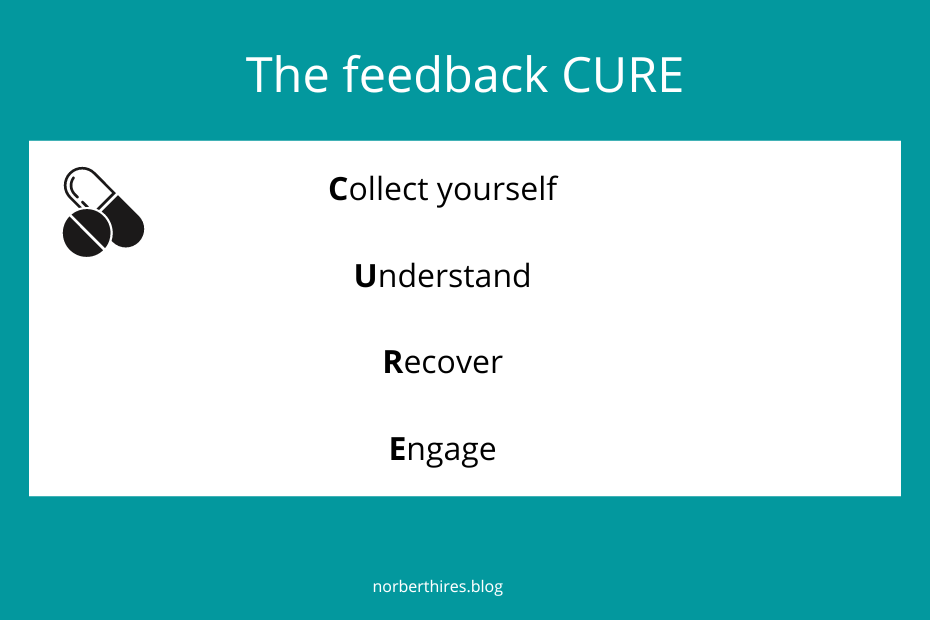

The feedback CURE

Receiving and actually listening to feedback is one of the hardest skills to master. I have my fair share of challenges when it comes to feedback, especially when it is negative feedback.

In Crucial Conversations, we receive again an acronym that explains why it is so hard to receive feedback and gives a tool in our hand to CURE our feedback-receiving muscles.

The feedback CURE has 4 stages:

- Collect yourself. After receiving any feedback you should take a deep breath. We tend to perceive feedback as a direct attack on us, but slow breathing signals that you are safe, and you don't need to prepare for self-defense.

- Understand. You got the feedback. You are calm, but now be curious about the feedback you received. Ask for examples and further explanations. Don't make it personal and disconnect the person giving the feedback from the feedback itself. Take it for granted that the person giving the feedback has your best interest in mind.

- Recover. Deeping slowly does not automatically mean that you can think through the feedback logically. If your feelings get out of control ask for a pause and take some time to process the feedback.

- Engage. After recovering from the received feedback, notice the giver of the feedback what you accept from the feedback, and whether you want to commit to change that or not.

How to finish?

If you managed to keep the conversation in a safe environment, you stated the problem clearly, you listened to every voice and you are ready to move forward with the solution, then the only thing left is to finish the crucial conversation by committing to an action.

Move to action

There are four common ways of making decisions:

- command,

- consult,

- vote,

- and consensus.

Regardless of which method you choose, it is worth forming clear commitments about the result of the conversation. To make it clear what is expected from whom, use the WWWF acronym:

- Who?

- Does what?

- By when?

- How will you follow up?

Crucial Conversation: Summary

Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High is a book that provides practical knowledge on how to engage in important conversations effectively.

The authors emphasize the importance of addressing opposing opinions accompanied by strong emotions in order to improve relationships and organizational performance.

The book suggests that the ability to hold relevant crucial conversations can predict the success or failure of a project. It provides strategies for choosing the right topic, focusing on the real issue, and reframing clever stories into useful ones.

It also offers advice on making conversations safe, listening actively, receiving feedback, and taking action. The book ends by emphasizing the need for clear commitments and follow-up after a crucial conversation.