How to Shift Your Perspective and Get Unstuck? (The Art of Possibility Summary)

Have you ever felt stuck in your life? Have you ever felt the urge to change but didn't know where to start? The Art of Possibility gives you the tools to answer these questions.

I hate self-help books in which the author picks a popular problem, shares his way of solving it, and creates a framework around his thinking.

These types of advice are often not applicable to my life, so reading them turns out to be a waste of time.

This is not the case for The Art of Possibility.

The conductor Benjamin Zander and his therapist wife Rosamund Stone Zander did something remarkable with their book. Instead of picking problems they are telling stories from their life and career while sharing exercises on how you can shift your perspectives to enable a life of possibility.

I am good at picking a goal and executing it, but often I got stuck in the process. Challenges often require a different type of me and it happens that I don't see the opportunities because I limit my thinking by always pushing forward.

I picked up The Art of Possibility to help me bring new perspectives into these situations and recalculate what is important to me.

The Lessons of The Art of Possibility

- Create your own rules in life

- Escape the Measurement World

- Give an A beforehand

- Becoming a Contribution

- Leading from any chair

- Don't take yourself so goddamn seriously

- Embrace The Way Things Are

- Giving Way to Passion

- Enrolling

- Being the Board

- Frameworks for Possibility

- Telling the We Story

1. Create your own rules in life

Most situations in life are governed by rules that were created by our fellow humans.

We pick a career based on the values that we saw, embrace the rules of chess and play by them, or push through an arbitrarily created career ladder.

Most of these rules are not driven by physics but governed by the assumptions of others. And if so why don't we change our perspectives and create rules about life that serves us better?

Especially when playing by others rules is not getting the job done.

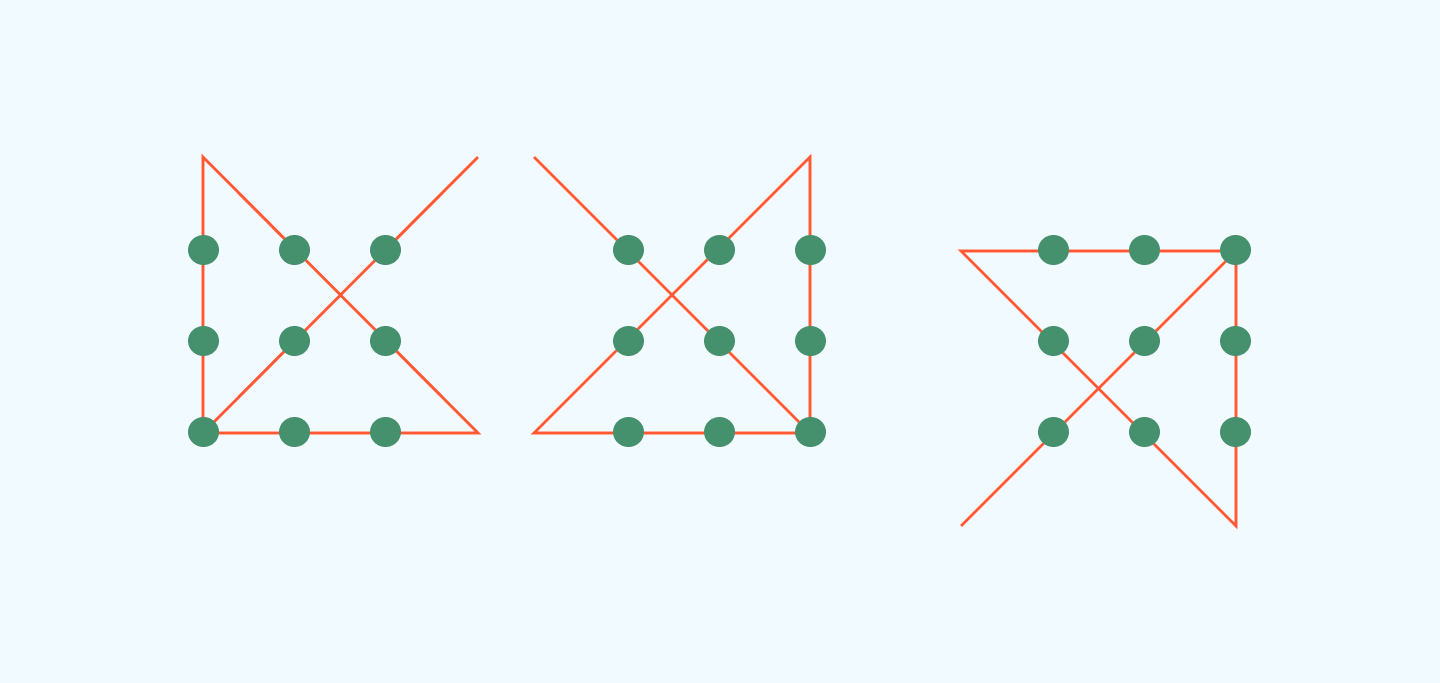

How do you connect 9 points with 4 lines?

I intended to solve this challenge by drawing big and small squares and triangles within the frame provided. I was working with the rules I believed were provided with this exercise: think with and within the points.

But to solve this challenge we need to surpass thinking about the 9 points and embrace the fact that we have 4 lines.

We connect the points by thinking outside of the box (literally).

We often encounter situations in life when the assumed rules of the games are making it hard or even impossible to play. Acknowledging that most of these rules are invented and we can come up with our own rules can help us get closer to the solution.

The Practise of Inventing Your Own Rules

Ask the following questions

- What assumptions am I making?

- That I am not aware I'm making?

- That gives me what I see?

Followup Questions:

- What might I now invent?

- That I haven't yet invented?

- That would give me other choices?

2. Escape the Measurement World

We live in a world of measurement. We need to get good grades, pass tests, increase revenue, and perform better than our rivals. Our success is often determined by using numbers, but these also limits our thinking.

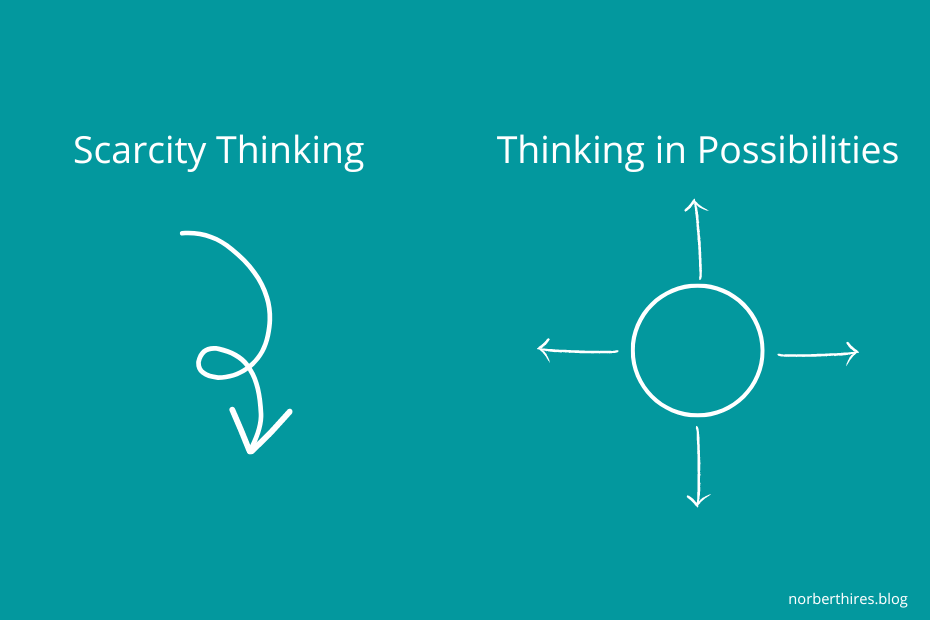

Living in the measurement world leads to scarcity thinking.

We are told that we need to acquire more to survive and resources are limited. But in several cases, these are made-up rules and in fact, everyone can have enough to get by, let alone thrive.

Escaping the measurement world is similar to switching from finite games to infinite games.

The Practise of Escaping the Measurement World

Ask yourself:

- How are my thoughts and actions in the moment shaped by the measurement world?

- How does it limit you?

- How can you overcome it?

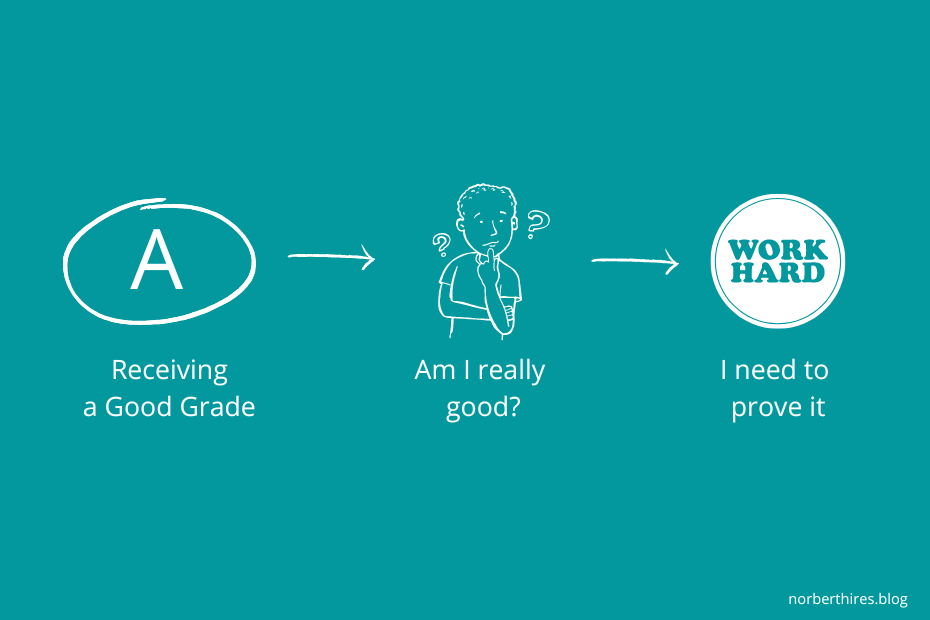

3. Give an "A" beforehand

Benjamin Zander is not just a conductor but an educator and as one you would think he could not escape the grueling habit of grading students to pass his class.

Though he escaped the measurement world and turned grades into an exercise we can use in our own life.

He gives an A automatically to his students who write a letter as their future selves on why they deserved to receive an A.

It is not about the grade (which is an arbitrary number anyway).

It is about assuming the best of others.

Is Tanya cynical or passionate?

After practice, Benjamin asked a violinist Tanya, whether there was any problem with the piece. She played perfectly but her posture and way of looking signaled that something is off.

Tanya suggested that the tempo is too fast for the violin. The conductor changed it to be slower. Tanya liked Mahler's Ninth Symphony so much she was caring about it, that's why it was reflected in his posture.

Benjamin gave an A beforehand in this situation which enabled them to get a better concert at the end instead of blaming someone from the start.

"I learned from Tanya that the secret is not to speak to a person's cynicism, but to speak to her passion"

The Messiah is one of you

The Pygmalion effect is a psychological observation that states that bad expectations lead to bad performance while good expectations trigger good performance.

The authors bring the story of a struggling monastery to demonstrate the power of Giving A's with connection to the Pygmalion effect.

A monastery was going through a hard time. The five monks living there were getting older and none wanted to be a monk there anymore. They didn't treat each other well.

The Abbot went to ask the nearby synagogue's rabbi for advice.

The Rabbi told him:

"I have no advice to give. The only thing I can tell you is that the Messiah is one of you."

The Monk told this to his peers. They started to treat each other respectfully because one of them could be the Messiah. And the change was noticeable by others: more visitors came and they saw inspiration to become a monk.

4. Becoming a Contribution

During dinners, the author's family asked the kids how was their day. They always answered with what they accomplished.

This created tensions between the kids and put pressure on them regardless of how much they got done.

Benjamin Zander changed the script"

- instead of asking: What have you accomplished?

- he asked: How was I a contribution today?

Be loved for who you are not what you do.

The upside of being a contribution is not measurable in fame or in money. The winner of the contribution game receives a different kind of prize, which is more unpredictable but much more rewarding.

The Practise of Being a Contribution

- Declare yourself to be a contribution.

- Throw yourself into life as someone who makes a difference, accepting that you may not understand how or why.

5. Leading from any chair

Benjamin Zander is conducting orchestras for more than 40 years. His work is not directly visible and he does not make a sound during the concert.

His job is to make others perform better.

And he can do that far away from the lights.

"A leader does not need a podium; she can be sitting quietly on the edge of any chair, listening passionately and with commitment, fully prepared to take up the baton."

6. Don't take yourself so goddamn seriously

This exercise resonated with me immensely as I am someone who takes himself too seriously. If you received anytime in the past to "smile more darling", then you will appreciate this message as well.

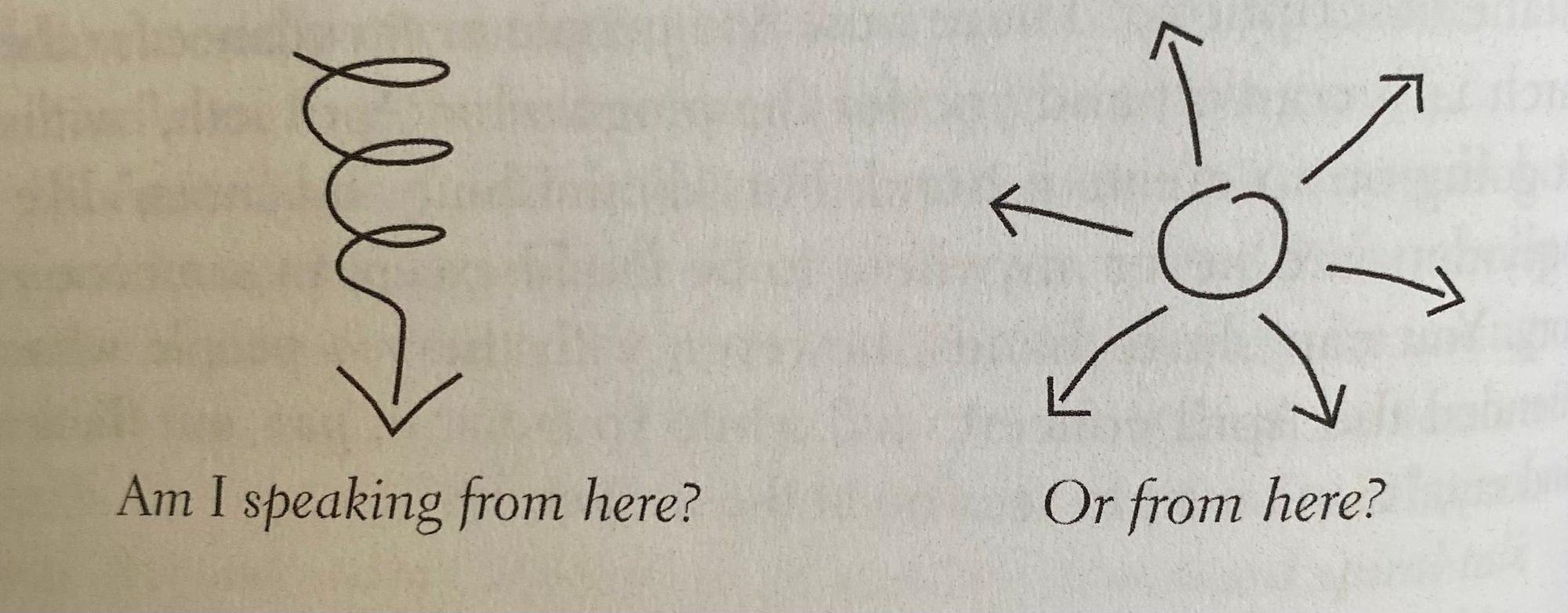

The Calculating Self is our childish part who would do anything for survival. He thinks about challenges, improvement, and positioning himself well in the hierarchy. He wants to ensure his survival. But we are not kids anymore and it is barely the case that we are in constant survival mode.

On the other hand, the Central Self is extremely generous, creative and is a true representation of our values. This part of us helps us free our Calculating Self.

Our thinking is a constant fight between our Calculating Self and our Central Self and more often than not our boring Calculating part wins. But we start by default in calculating mode, so if we come across anything hard to tackle we got stuck.

Finding the solution often requires asking our Central Self.

The practice of being less serious

When you are deep in the trenches ask yourself the following question:

What would have to change for me to be completely fulfilled?

The Calculating Self can not deal with this question because it can point out the insignificance of our daily struggles. This exercise takes the burden off our shoulders and brings a much-awaited change in perspective.

7. Embrace The Way Things Are

In the movie Babe it is Christmas on the farm. The animals are watching how one of them got chosen to be the main dish of the festive table.

Ferdinand, the duck is complaining about why it had to be his friend, Roseanna. The wise cow put Ferdinand in its place by suggesting that the only way to happiness is accepting the way things are.

The way things are stinks! - finishes the duck.

"The practice in this chapter is an antidote both to the hopeless resignation of the cow and to the spluttering resistance of the duck. It is to be present to the way things are, including our feeling about the way things are. This practice can help us clarify the net step that will take us in the direction we say we want to go."

If you accept your situation then you are free to ask:

What do I want to do starting from here?

- If your car breaks down you can still decide to have the most enjoyable hike of your life.

- If it is raining you can choose to cook the best meal your family ever saw.

The Seventh Rule is quite similar to stoicism's dichotomy of control which states that we should focus on only things within our control.

“Some things are within our power, while others are not. Within our power are opinion, motivation, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever is of our own doing; not within our power are our body, our property, reputation, office, and, in a word, whatever is not of our own doing." - Epictetus

Though it is worth pointing out that embracing the present moment (which often comes with challenges) can lead to scarcity thinking. Scarcity thinking can pull us into a downward spiral.

In this situation, it makes sense to ask:

8. Giving Way to Passion

The practice of this chapter, giving way to passion, has two steps:

- The first step is to notice where you are holding back, and let go. Release those barriers of self that keep you separate and in control, and let the vital energy of passion surge through you, connecting you to all beyond.

- The second step is to participate wholly. Allow yourself to be a channel to shape the stream of passion into a new expression for the world.

9. Enrolling

Our conductor author once met with a leader of a corporation without agenda. Sure, it is always great to secure sponsors for his next concert, but this wasn't on the table.

During their discussion, the businessman shared that he is sponsoring a government program to improve the conditions of youths in poor neighborhoods.

Benjamin wanted to help, he organized lectures on music and invited the kids to one of his concerts. He was onboarded by the mission, not by the prospect of sponsorship, and had a great impact on hundreds of kids.

The Practise of Giving Way to Passion

The practice of this chapter, giving way to passion, has two steps:

- The first step is to notice where you are holding back, and let go. Release those barriers of self that keep you separate and in control, and let the vital energy of passion surge through you, connecting you to all beyond.

- The second step is to participate wholly. Allow yourself to be a channel to shape the stream of passion into a new expression for the world.

Benjamin is a passionate educator besides being a conductor.

Leaning on his passion and helping children sparked others to do the same.

The program was a great success in the end.

10. Being the Board

There are more metaphors in strategy books about chess than about anything else. But I have to admit chess provides a great framework to think about risks and actions.

The authors are encouraging us that instead of looking at ourselves as a chess piece, we should zoom out and identify ourselves as the board itself.

"When you identify yourself as a single chess piece and by analogy, as an individual in a particular role - you can only react to, complain about, or resist the moves that interrupted your plans. But if you name yourself as the board itself you can turn all your attention to what you want to see happen, with none paid to what you need to win or fight or fix."

Own the risk

They also suggest "owning risks" which come with our decisions.

If you build your house near a river and the flood damages your home then it is not the river's fault that it occasionally leaves its bed.

If you own your decisions then you will not position yourself as a loser of an unfortunate event but you can start to think about how to avoid that in the future.

Enroll people on your board

A violinist didn't show up for a community orchestra rehearsal and three other violinists messaged to be sick. With that many violins missing the success of the concert came into danger.

Cora, the violinist though was in the school during the rehearsal but didn't attend. The conductor confronted her about her irresponsibility and why she does not do what he wants her to do.

The violinist quit the orchestra because of this treatment.

Benjamin wrote a "Give A letter" to Coda.

He didn't ask her back, just acknowledged his mistakes in wanting to control everything.

Instead of letting one person go (which could have happened even after writing the letter), Benjamin spent hours crafting a letter to one musician out of hundreds he works with. He prioritized connections over time.

11. Frameworks for Possibility

A girl in school went through chemotherapy and became bald. She put on a scarf, but other kids pulled it off and made fun of her. The teacher arrived the next day bald (she shaved off her hair). Then the rest of the children begged their parents to be able to shave their heads.

The teacher changed the framework of possibility.

Being bold became a fashion statement, a cool thing, which the kids felt compelled to follow.

The criterias of a good vision

Visions serve as the biggest enabler of possibility and the motivating force anyone can be hyped on.

Yet more often than not companies define vision statements that are not compelling enough, or they put scarcity thinking into their goals (be the market leader, be the best) which does not count as a vision.

In The Art of Possibility, we receive a comprehensive list of what a good vision should look like:

- A vision articulates a possibility.

- A vision fulfills a desire fundamental to humankind, a desire with which any human being can resonate. It is an idea to which no one could logically respond, "What about me?"

- A vision makes no reference to morality or ethics, it is not about a right way of doing things. It cannot imply that anyone is wrong.

- A vision is stated as a picture for all time, using no numbers, measures, or comparatives. It contains no specifics of time, place, audience, or product.

- A vision is free-standing - it points neither to a rosier future, hor to a past in need of improvement. It gives over its bounty now. If the vision is "peace on earth," peace comes with is utterance. When "the possibility of ideas making a differ-ence" is spoken, at that moment ideas do make a difference.

- A vision is a long line of possibility radiating outward. invites infinite expression, development, and proliferation within its definitional framework.

- Speaking a vision transforms the speaker. For that moment the "real world" becomes a universe of possibility and the barriers to the realization of the vision disappear.

12. Telling the We Story

During a dinner with students, the author's father Walter Zander shared the stories of Jews and Arabs. He launched 2 different threads which arrived at the end in the same place: Israel.

He talked about Abraham, the Bible, and all the possibilities from the point of view of Jews. And then he went on to start the same story with the Tales of the Arabian Nights, the architecture, the library of Alexandria.

He was speaking with equal enthusiasm regardless of whose story he was sharing and he finished his lecture when the two nations' paths collided in Israel by telling:

"Such an opportunity for great nations".

We rarely think of We.

Or the We immediately pairs with Them to signal a conflict. The practice of the chapter enables us to quit groupthink and find hidden possibilities for all of us.

The WE Practise

- Tell the WE story- the story of the unseen threads that connect us all, the story of possibility.

- Listen and look for the emerging entity.

- Ask: "What do WE want to have happen here?"

"What's best for US?" _all of each of us, and all of all of us.

"What's OUR next step?"

The Summary of The Art of Possibility

- Invent new rules in life that open up new possibilities.

- Escape the measurement world and the scarcity thinking that comes with it.

- Give others an A beforehand and assume the best of them.

- Focus on being a contribution rather than just what you accomplish.

- Lead from any chair and make a difference without needing a formal position of authority.

- Don't take yourself too seriously and let go of the need to always be calculating and strategic.

- Embrace the way things are and accept the present moment, including our feelings about it.

- Give way to passion and let go of barriers that hold us back.

- Enroll others in our mission and inspire them to participate with passion.

- See ourselves as the board, not just a chess piece, and take ownership of risks and decisions.

- Create frameworks for possibility and define compelling visions that resonate with everyone.

- Tell the "we" story and look for possibilities that benefit all of us, not just one group.