The Cold Start Problem - Book Summary & Review

The most popular products are not competing on features. Their now competitive advantage is what made them challenging to get traction in the early days: the network. How to build and scale a networked product? The Cold Start Problem is the book with the answers.

There are several companies strongly relying on their network. Airbnb, Tinder, Uber, Facebook, and the list goes on. None of them would be as valuable today as they are without their interconnected user base or dense inventory.

Regardless of their market type, they share certain characteristics and often face the same challenges.

Andrew Chen, general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, who led Rider Growth at Uber earlier took the challenge to write the ultimate guide to networked products.

I suggest you read the book by yourself. The stories give context to the observations and laws described in the book.

Also, I do not intend this article to be a comprehensive summary of The Cold Start Problem but a review of the most important takeaways based on my interpretation.

Why should you care about network effects?

"Humans are the networked species. Networks allow us to cooperate when we would otherwise go it alone. And networks allocate the fruits of our cooperation. Money is a network. Religion is a network. A corporation is a network. Roads are a network. Electricity is a network." - Naval Ravikant

- Network principles are applicable in other industries: “I found that people were repeating the same ideas and concepts, and observed that they were recurring throughout multiple sectors. You could talk to someone who spent their career working on social networks, and find that they had ideas that were equally applicable to marketplaces.”

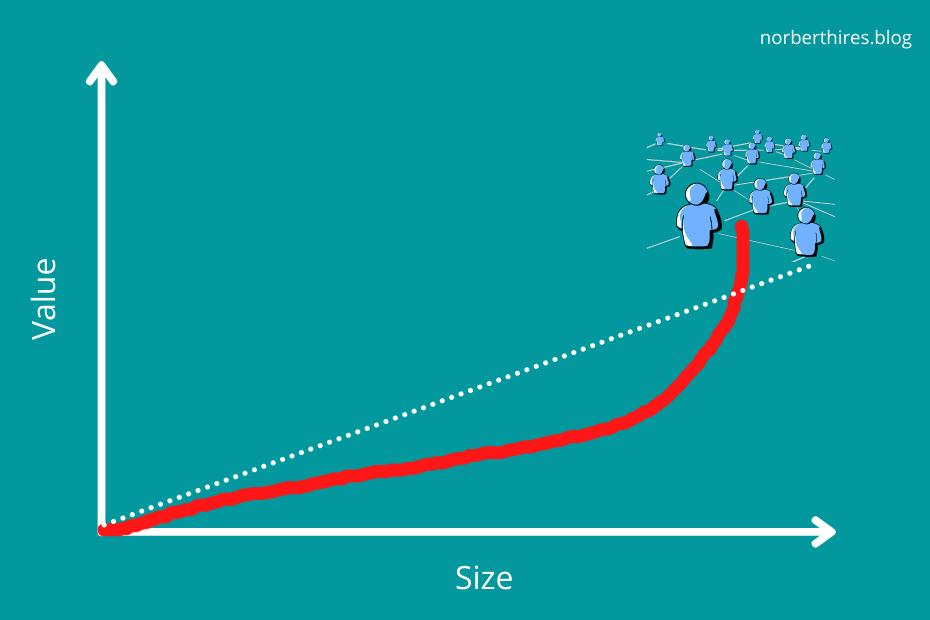

- Network effects make products more valuable: The network effect describes when a product gets more valuable by increasing its size. Network effects cause higher engagement and often faster growth. Youtube without a high number of videos wasn’t as compelling as it is now. A social network without your friends on it just doesn’t cut it either.

- Network effects as a protective layer: For consumer product competition is fierce and the defensive barriers are low. Anyone can start a new app or copy a feature. The only protective barrier left is your network.

Metcalfe's Law

Metcalfe's Law is a popular idea that states that the systemic value of compatible communicating devices grows as a square of their number. The concept was used during the dot-com boom to justify enormous valuations.

In reality, there are weak advantages of being first. In most of the markets the winner usually doesn’t take all, it has to compete with smaller players on different user segments and geographies.

Allee threshold

To make the point for the real advantage of networks Andrew Chen borrows an observation from ecology. In the 1930s, an American ecology professor, Warder Clyde Allee published a paper with the name “Studies in animal aggregations: Mass protection against colloidal silver among goldfishes”.

The Allee threshold is based on the observation that animals are safer and grow faster in groups.

- Goldfish can resist water toxicity when they are in groups.

- Meerkats can warn each other of danger.

Allee threshold functions as a tipping point and we can observe it in technology as well. A messaging app that doesn’t reach the threshold (doesn’t have enough people using it) won’t be able to retain its users and will lose more eventually.

Cold Start Theory

Andrew Chen uses five stages to describe the typical lifecycle of a networked product.

1. The Cold Start Problem

The first phase is what every product faces: they don’t have users.

Besides using spreading the word in your own network, using marketing, and utilizing growth hacks there are some shortcuts to the Cold Start Problem.

You can solve the Cold Start Problem

with Partnerships

Microsoft used its partnership with IBM to establish a presence on a much broader scale than its resources would have made possible without IBM. They created a custom product to get started and took advantage of network effects when no one was aware that things like that exist.

with Bundling

You can use an existing user-base to solve the Cold Start Problem.

Bad example: Google used its resources and vast user base to promote their new social media-like product: Google+. They put Google+ icons everywhere and drove a high number of their users to the new product. But Google+ eventually failed. The top-level numbers were good but the engagement wasn’t. Users clicked on the icon but didn’t use the product. Eventually, Google shut down Google+.

Good example: What Facebook did with Instagram is a good example of bundling. Enabling sharing photos in both network users could reach more of their followers while Facebook and Instagram could use this synergy to have more content on their platforms.

with Fake it till make it

Airbnb scraped ads from Craigslist to have content in the early days.

Doordash and Postmates showed restaurants on their platforms that actually didn’t sign up for their services. When someone ordered from one of those restaurants, their couriers would simply pick up the order as an ordinary customer and deliver it for those who order it.

with consulting

In the book, the author doesn’t describe consulting as a way of solving the Cold Start Problem but rather a method that can help to work on the right problems.

Andrew Chen borrows the word of Paul Graham who advocates consulting as a way of reaching product/market fit.

“By building the functionality they need on an ad hoc basis, and then generalizing, they have a better chance to hit product/market fit—even though this approach won’t scale.” - Paul Graham

2. Tipping Point

Solving the Cold Start Problem means you found the smallest segment where networks can be found, your Atomic Network (is this a reference to Atomic Habits?).

As the network grows, it gets easier to capture a bigger chunk of the market. The most successful networked products grew on a network-by-network basis. Airbnb from city to city, Tinder from college campus to college campus, and Slack from company to company.

3. Escape Velocity

Andrew Chen describes the Escape Velocity phase by its underlying forces:

- “the Acquisition Effect, which lets products tap into the network to drive low-cost, highly efficient user acquisition via viral growth;

- the Engagement Effect, which increases interaction between users as networks fill in; and finally,

- the Economic Effect, which improves monetization levels and conversion rates as the network grows.”

4. Hitting the Ceiling

Solving the Cold Start Problem and growth supported by network effects are not enough to dominate a market or even to be in the game for the long term.

Based on interviews with operators of such companies, we know that a growing network wants to both grow and tear itself apart.

Spammers and fraudsters appear and the need for network maintenance increases. Without spam detection and the curation of content, a network can easily become unstable.

Also scaling a networked product after product/market fit requires much more effort than reaching product/market fit. Instagram famously had 13 employees when it was bought by Facebook, but scaling the product to its full potential requires more effort.

5. The Moat

“The final stage of the framework focuses on using network effects to fend off competitors, which is often the focus as the network and product matures.”

During this phase we already have a matured product that faces new kinds of challenges:

- Market Saturation.

- Churn from early users.

- Bad behavior from trolls, spammers, and fraudsters.

- Lower-quality engagement from new users.

- Regulatory action.

- A degraded product experience, as too many users join. When users are leaving a network as fast as new users sign up, then top-line growth naturally slows.

- The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs: The effectiveness of ads is decreasing over time.

Atomic Network

An Atomic Network is the smallest segment when networks can be formed. It was universities for Tinder, cities for Airbnb, drivers around a specific location for Uber.

The first atomic network of your product is probably smaller than you think.

For Uber, it wasn’t a driver in a city or even a driver near a location. Uber’s atomic networks were drivers around a specific location at a given time like “5pm at the Caltrain station at 5th and King St.”

Motivations to use networked products

Besides obvious reasons like financial incentives and solving a problem, sometimes products without any of those see high engagement. Some of these are connected to the way networks function.

As part of a network you have other incentives besides the obvious ones:

Displaying status

If you can display your status with the app, it can alone serve as an incentive to use it.

The majority of Instagram users don’t earn any money from their posts, yet they are eager to share their photos of adventures, cars, and concerts to show them to others.

Community, feedback

Why are a small minority of Wikipedia users editing the majority of the site's pages without any financial incentives?

Andrew Chen makes a guess that it is maybe due to Wikipedia’s community itself.

“Wikipedia’s content creators are likely motivated by the community itself. Social feedback, status, and other community dynamics encourage editors to keep creating content.”

The hard-side make or break products

“The hardest problem to solve in creating the first atomic network is, well, attracting the hard side. Focus on attracting content creators to a new video platform, or sellers to a new marketplace, or the project managers inside a company to a new workplace app. The other side of the network will follow.”

Subsidies for the hard side

Attracting the hard side often requires subsidies.

When Microsoft launched its streaming service it paid Ninja, a popular streamer with millions of followers a huge sum to use the platform.

Come for the Tool, Stay for the Network

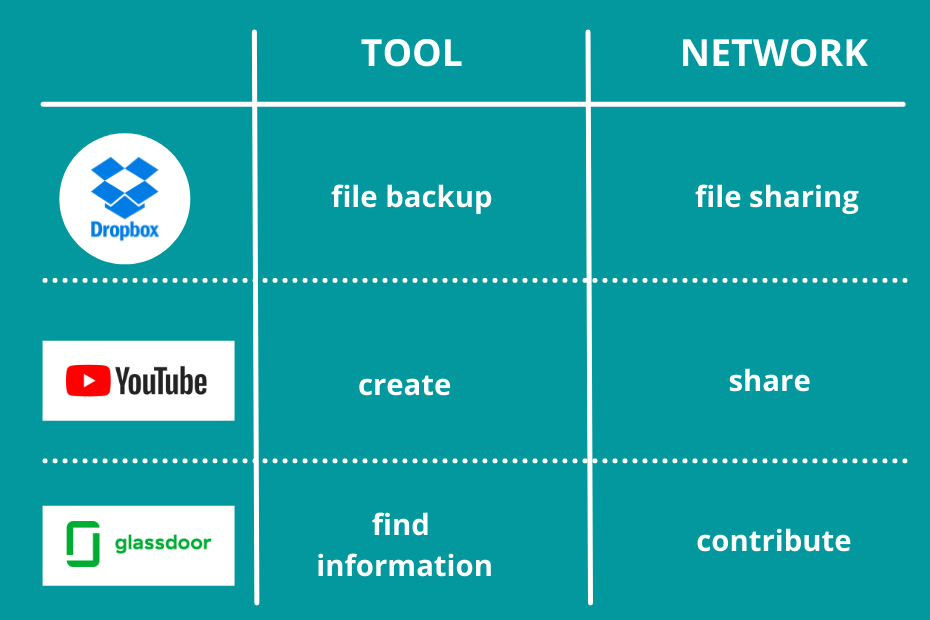

Chris Dixon writes in a 2015 essay about a new strategy:

“The idea is to initially attract users with a single-player tool and then, over time, get them to participate in a network. The tool helps get to initial critical mass. The network creates the long term value for users, and defensibility for the company.”

Dropbox was used as a file backup service first (tool), but became a way to share files with colleagues (networks).

Other examples:

- Tool, network Create + share with others (Instagram, YouTube, G Suite, LinkedIn)

- Organize + collaborate with others (Pinterest, Asana, Dropbox)

- System of record + keep up to date with others (OpenTable, GitHub)

- Look up + contribute with others (Zillow, Glassdoor, Yelp) Each

Advantages of the invite-only strategy

Why would anyone limit his growth by enabling a service only through invites?

Andrew Chen has some strong points on this:

- FOMO: Invite only strategies built on the fear of missing out, however, this is not the core driver why invites are working so well.

- Curated network: New networks with a big launch often fail because they have a lot of unconnected users. Invites make sure to have only connected users in the network.

- The advantage for early users: Early adopters of networked products can be part of a community with high-quality connections and also have the possibility to go viral organically.

- Less load on servers: With an invite-only launch you can control how many people you let use your product and avoid server overload in the early days.

When a Product becomes an Economy

When a network scales its hard-side will professionalize. More users will be able to make a living from the product. Full-time content creators, tiktokkers, drivers, freelancers, and Airbnb hosts appear.

“When a network becomes large, rich, and diverse, it’s often described as an “Economy”—you may have heard about the Gig Economy, the Attention Economy, the Creator Economy, and so on.”