Review and Notes: The Undercover Economist by Tim Harford

What happens to our money when inflation is high? How do public investments affect unemployment? Who prints the money and how does its quantity affect it? What is more important: happiness or money?

All interesting questions, often with dry and boring answers. But not in Tim Harford's book.

Imagine being promoted to the head of an economy.

- What would you want to achieve with that kind of power?

- What do you think is important?

- By what means do you want to achieve your goals?

Whatever your answers to these questions, sooner or later your decisions will have economic consequences.

While investment and finance books that top the bestseller lists benefit from personal experience, when it comes to macroeconomic issues, our experience as ordinary people adds little to our understanding of how an economy works.

This undercover economist talks about macroeconomics in a way that makes it interesting for people who know nothing about economics. The author asks questions that have only practical relevance and are likely to occur in the minds of ordinary people, and then answers them, sometimes anecdotally, sometimes succinctly.

Tim Harford: The Undercover Economist

Exposing Why the Rich Are Rich, the Poor Are Poor and Why You Can Never Buy a Decent Used Car!

Some of the topics covered:

- printing money

- the functioning of central banks

- unemployment

- crisis management

- money and happiness

In the remainder of this book review, I highlight some interesting parts of the book.

If this short introduction has piqued your interest in The Undercover Economist and you don't want to spoil your reading experience, you can should stop here.

In writing this summary, I have tried to highlight the most useful and interesting parts of the book, which you may find useful even without reading the book. I have omitted explanatory anecdotes and chapters that I thought were less important.

But let's see what we can learn from the undercover economist:

Reasons for a strong economy

You are the number one decision-maker in an imaginary country. Whatever you want to achieve, your country's economy influences everything:

- Want to raise the quality of education? Rich countries are the ones that can afford a good education system.

- Want to fight hunger? Then ask yourself: is hunger more common in poor or rich countries?

If you are thinking primarily about welfare issues and want to help the citizens of your imaginary country in areas seemingly unrelated to the economy, you cannot avoid the economy.

A strong national economy allows you to think about other issues.

The moral implications of recession

Recessions also have non-pecuniary costs. According to Benjamin Friedman, an economist at Harvard University, recessions have moral consequences:

- people feel insecure and unhappy,

- and charitable giving declines,

- nepotism, racism, intolerance, and other forms of exclusion increase,

- and with them anti-democratic forces.

The illusion of inflation

Even if we understand that we should always take account of monetary depreciation (aka inflation), in practice we are simply unable to adjust our figures for inflation.

Inflation-adjusted numbers often lack the emotional charge to be able to influence our behavior.

For example:

- If we get a pay rise, but the rise does not exceed inflation, our pay will effectively fall. Yet we celebrate such a "raise".

- In a deflationary environment, where the price level of goods is falling (so our money is worth more), we are unable to swallow even a small pay cut, even if the purchasing power of our salary remains unchanged.

We often only see the + and - signs.

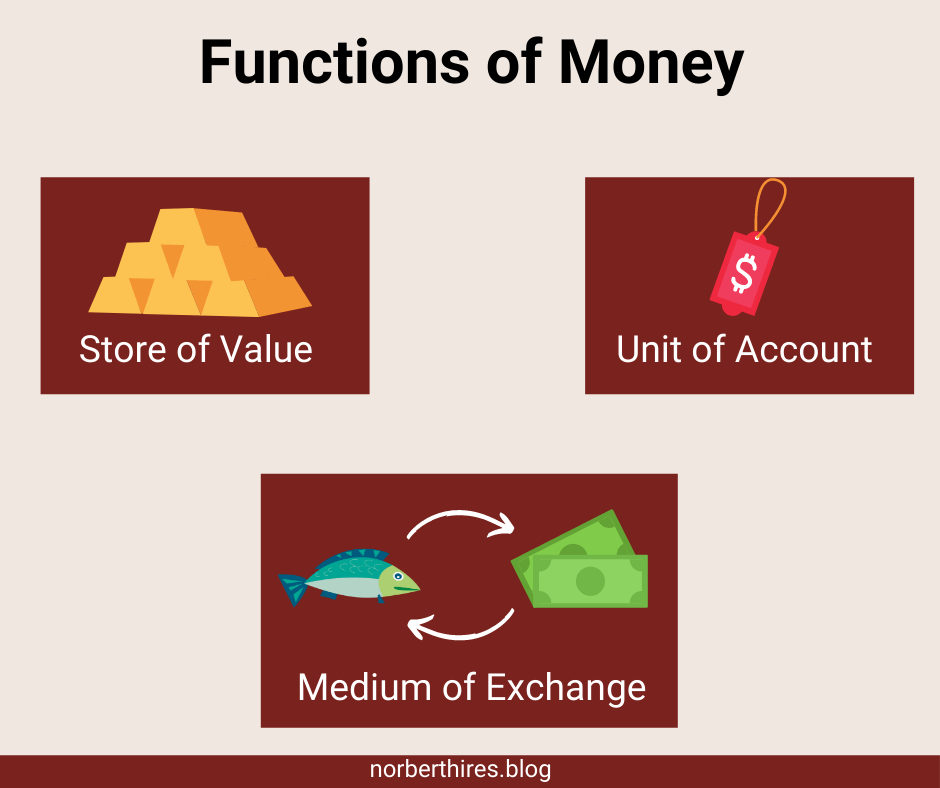

The Three Roles of Money

According to the textbook definition, money has three functions:

- Unit of Account

- Store of Value

- Medium of Exchange

Each of these functions can be separated from the others in certain circumstances (money can have only one function), but the best money has all three functions at the same time.

Money as a circulating medium allows us to move our purchasing power through space. The money we earn by saving (if we earn our living by saving) can be used in another situation, for example, to buy a computer.

Money as a measure of value allows us to shift our purchasing power over time. Roman soldiers, for example, often received their pay in salt, because salt held its value for a long time.

The Roman soldiers' salaries are also the origin of the English word salary.

- Salt - Sal - Salary

Inflation and the liquidity trap

What happens if the inflation target is high?

What the central bank is saying is: "Once we get out of this liquidity trap, you better believe that prices will rise and the money in your pocket will be worthless."

This helps because fear of future inflation encourages people to spend their money now before its value melts away.

The record holder: Hungary

Hungary holds the world record for the highest monthly inflation rate ever. In July 1946, inflation was 41,900,000,000,000,000,000 percent.

That means prices are tripling every day, and you wouldn't buy a cup of coffee for a month's salary if you waited a week to spend it.

Investment, labor, economy

In a recession, you might decide that your imaginary government should try to boost the economy by hiring an army of workers. But you'd be out of your mind if you gave them some pointless task, like burying chocolate coins.

No. You'd hire them for mundane and meaningful-sounding things like street sweeping, street policing, or building new streets.

Imagine that you still spend a million dollars burying chocolate coins, but the private sector doesn't shrink at all (you're not sucking labor away from the private sector because, for example, unemployment is high). In that case, every dollar spent makes the economy itself a dollar bigger. In the jargon, the spending multiplier is one.

In theory, if you want to make sure that money is spent to boost the economy, the best way is to spend it yourself.

Happiness and money

Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize-winning psychologist in economics and author of Thinking Fast and Slow, has published a study with Angus Deaton that sheds some interesting light on the relationship between money and happiness.

Kahneman and Deaton found that higher-income correlates with life satisfaction without limit - but beyond an income of around $75,000 a year, extra money does not improve mood.

Most psychological research on economic conditions concludes that (after a certain minimum is reached) money alone has a modest effect on people's life satisfaction, but that getting a job is a more important consideration.

The policy implication of the happiness research should be those policymakers should try to reduce unemployment, because unemployment is an extremely distressing experience.

Competition is desirable

Many industries are in one way or another comfortably protected from competition, even though the pressure generated by competition is a good way to improve the quality of management - and also to reduce prices, increase demand for skilled workers and promote innovation.

The Easterlin paradox

Easterlin's paradox states that while richer people are happier than poorer people, richer societies are not happier than poorer societies.

Put another way, if you get a 10 percent wage increase, you will be happier. But a 10 percent economic increase will not make those around you happier.

Another way of interpreting Easterlin's paradox is that what makes people happy is not so much income, but status. Life is a zero-sum game in the sense that if you climb up the ladder, someone else has to slide down - and that status is closely related to income.

The Future

Because of advances in technology, a single skilled worker can do more today than a worker ever could before. Meanwhile, unskilled workers are becoming a burden rather than a resource.

This is why education is important. The quality of education is crucial to the success of the economy and the well-being of individuals.